Addressing the complexities of homelessness in Northern York County

|

|

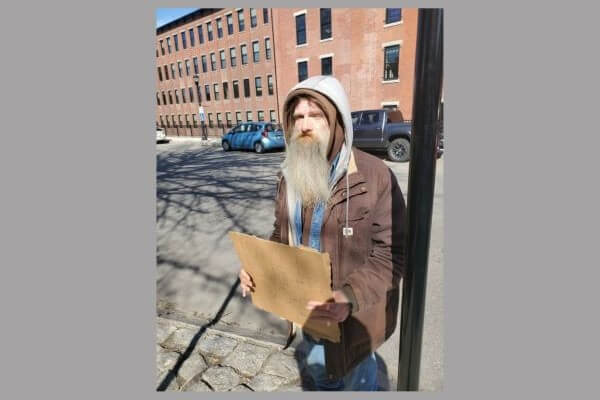

Robert, 57, stands at the intersection of Main and Lincoln streets in Biddeford, hoping to raise a little bit of money and find some work. PHOTO BY RANDY SEAVER

|

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of stories about homelessness in northern York County.

Citing a lack of both resources and guidance from the federal and state governments, Biddeford City Manager James Bennett recently said the issue of homelessness is “probably the most difficult issue” that any municipality in Maine can face.

And while some social media users say the city of Biddeford and surrounding municipalities are “doing nothing” to solve the crisis, others say that expanding resources will simply draw more unhoused persons to the area, placing an even greater strain on local resources and taxpayers.

“There are a lot of factors that play into this,” said Biddeford Mayor Alan Casavant. “And there are no easy answers. In my opinion, we have a moral obligation to tackle this issue but we also have a fiscal obligation to the taxpayers. The question then becomes how do you reconcile those two things?”

Casavant said the issue of homelessness is becoming a larger issue in communities all over the country, and across the river in Saco, Mayor William Doyle agrees.

“We all want to tackle this issue, but it’s not as simple as just passing an ordinance,” Doyle said. “The problem is really aggravated by a lack of affordable housing in the region. If someone can’t afford to live in a house or an apartment, their options are limited.”

Doyle said the city of Saco is looking for a “comprehensive” solution, adding that he and members of the city council recently directed City Administrator Bryan Kaenrath to develop a list of recommendations for the council to consider regarding affordable housing.

“It’s pretty similar to what Biddeford is doing,” Doyle said, adding that proposals such as inclusionary zoning and other developer incentives are all “on the table” for discussion.

Earlier this week, the Saco City Council voted to approve moving forward with a Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) application that could clear the way for development of a 60-unit affordable housing development near the intersection of the Ross Road and Portland Road.

Kaenrath said he and his staff are “digging deep into the issue” in order to develop some “tangible and meaningful ways” to address what he acknowledged is a growing issue in the city.

“It’s not a problem that you can just throw some money at and have the problem solved,” Casavant said, pointing to other Maine communities that are still struggling with the unhoused crisis, despite spending millions of dollars to combat the issue.

According to the federal department of Housing and Urban Development, the number of people experiencing homelessness in Maine increased by more than 110 percent since 2020.

The Law Enforcement Perspective

Although the increasing number of unhoused people remains relatively hidden beneath the surface of day-to-day life, there is a growing strain on municipal services, including local police departments.

JoAnne Fisk, Interim Biddeford Police Chief, said there has been a spike in calls for mental health services since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic three years ago.

“Of course, that’s not all related to our unhoused population, but it is a factor,” Fisk said. “it’s not illegal to be homeless. We are constantly looking for ways we can adapt and better connect individuals with appropriate services and resources.”

Fisk said Biddeford recently hired a community engagement specialist to work as a liaison between the department and social service agencies, including the Seeds of Hope resource center.

Sgt. Steve Gorton has been working for the Biddeford Police Department for 27 years. Today, he heads up the community resource division for the department. He says issues related to the unhoused population “ebbs and flows.”

“There’s no question that more people are struggling, but I have not seen a big spike,” he said. “Our unhoused population experiences the same challenges as every one else, whether it’s domestic violence, assaults and theft. These issues are nowhere near unique to the unhoused.”

Gorton said police sometimes receive complaints about pan-handling near certain, busy intersections in the city.

“There’s not really much we can do,” he said. “It’s not illegal to pan-handle.”

According to the Bangor Police Department, nearly a third of annual police calls involve people experiencing homelessness and/or mental health issues. That city has also created mental health liaison positions within their police department.

The Lewiston City Council late last year voted 4-3 to create an ordinance that would prohibit people from sleeping on city property at night, between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m. That ordinance, which drew plenty of criticism from homeless advocates, is expected to go into effect on April 1.

On a recent warm afternoon, Robert, 57, stood on the corner of Main and Lincoln streets, directly across the street from Biddeford City Hall. He holds a sign he fashioned from a used pizza box: “Dammit! I need work.”

Robert said he moved to Maine a couple of years ago and has been struggling with alcoholism for many years. He said he is sober now, but that it is becoming increasingly hard to get “back on his feet.” When asked where he lives, he said he spends much of his time in Veteran’s Memorial Park.

“It’s degrading for a man my age to be out here begging,” he said. “It might be okay if you’re a young guy or something, but not for someone my age. Yeah, I made some bad choices, but now I have nothing. Literally nothing. I just want a job, but no one wants to hire a guy who doesn’t have an address or personal hygiene products.”

Bigger cities, bigger problems

“Some of Maine’s largest cities are spending a lot of money and still have a lot of problems,” Casavant said. “That does not mean that we can ignore the issue or just hope that someone else is going to fix it. I suspect that we’ll need to begin fixing a lot of little things that all contribute to the larger problem.”

By state law, every municipality in Maine is required to provide a General Assistance (GA) program to help residents with temporary emergency funding for things such as housing, heating and personal items. But even that program presents challenges for those on the bottom of the economic scale.

In order to receive GA services, applicants must demonstrate income and resource requirements. And although the city can provide temporary help for rental payments, it cannot provide housing or security deposits.

Municipal expenditures for General Assistance are funded by a 70 percent matching contribution from the state and 30 percent from the local community, presenting a bigger share of the problem for larger, service-center communities such as Bangor, Portland, Lewiston and Biddeford.

“It’s a regional issue,” Casavant said. “But unfortunately, it’s the larger communities such as Biddeford that have to bear the brunt of the cost.

Editor’s Note: Our next installment in this series will focus on state and regional resources for unhoused persons.

Randy Seaver can be contacted at [email protected].